The Titanic was filled with medical professionals either working as ship personnel or traveling in a non-professional capacity. There were also plenty of con artists aboard, hoping to worm their way into the wills of wealthy widows. Learn about their stories in this episode.

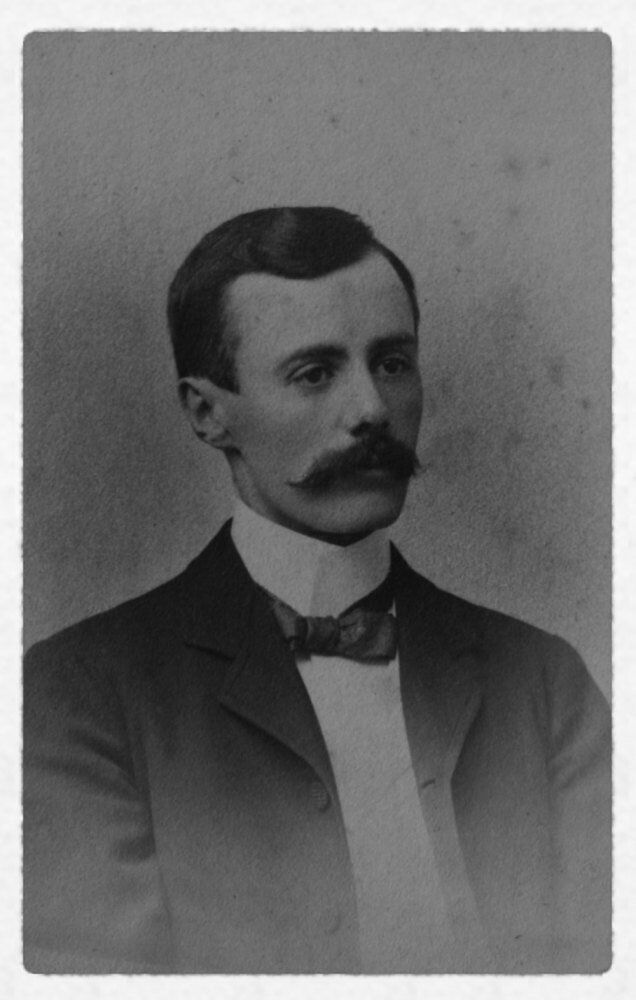

Dr. Ernest Moraweck– con artist who bilked several widows out of their family estates- traveled to Europe to look into how to use his inheritance that rightfully did not belong to him.

He met 2nd Class passenger Kate Buss, who was traveling alone. Her letters home from the Titanic indicate that she spent a good deal of her time on board with fellow second class passenger Ernest Moraweck, a doctor who was “known for inventing a tool to remove cataracts.”

Moraweck was the son of a baker who had emigrated from Bohemia to Chicago and later moved to Tell City, Indiana, where he opened The Hotel Moraweck, originally called the Steiner House. Moraweck’s wife Emilie died in 1904 at the age of thirty-three. At the time he sailed on the Titanic, Moraweck was living on a farm he’d recently bought in Frankfort, Kentucky. Kate Buss would describe Moraweck as “very agreeable.” He talked about his medical background, helped Kate get a bit of soot out of her eye, and offered to show her around New York City when the Titanic docked there. She said no thank you.

At 11:40 p.m., Kate Buss was reading a newspaper in her bunk. Suddenly she heard an unusual sound. “Like a skate on ice,” she recalled. Then, a bit later, she heard the engines reverse. Kate went into the hall— and there was Ernest Moraweck, standing right outside her door. “Would you like me to go and investigate?” he offered. “No thank you,” she answered. Kate sped away from Moraweck and quickly went straightaway to Marion Wright’s cabin. Marion would later recall that when the Titanic hit the iceberg, it sounded like a “huge crash of glass.” Then, when she heard the engines stop, it startled her even more. “The stopping of the engines on an ocean liner creates such a calm, such a painful silence, that it inspires passengers that something is not exactly right.” Kate and Marion went on deck together to find out what exactly was happening. Kate, Marion, & Sydney Collett survived; Dr. Moraweck did not. If his body was found, it was never identified.

He left behind an astonishing fortune of around $75,000—wealth that was allegedly amassed by swindling family estates away from lonely, unsuspecting widows no one else seemed to care about.

Dr. Henry Washington Dodge– survived & told of his experiences – said he saw First Officer Murdoch shoot others & then turn gun on himself.

He was 52 when the Titanic sank; Dodge survived but seven years later (1919) in San Francisco he had a break down shot himself in the elevator of his apartment building.

“Not a boat was launched which could not have held from ten to twenty-five more persons…. Some of the passengers fought with such desperation to get into the lifeboats that the officers shot them, and their bodies fell into the ocean.” – DR. HENRY WASHINGTON DODGE.

‘‘It was hard to realize, when dining in the large and spacious Dining Saloon, that one was not in some large and sumptuous hotel,” recalled first class passenger Dr. Henry Washington Dodge.

Dodge said there were no women in sight when calls for more women were made to board the lifeboats. He had gotten his own wife and son into a lifeboat earlier. He boarded Lifeboat 13, which was launched at about 1:35 a.m. Millvina Dean, an infant, was also in this lifeboat. She was the longest living survivor; she passed away in 2009.

Less than a month after the Titanic sank, at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco where he lived, Dr. Dodge gave his firsthand account of the sinking. The San Francisco Chronicle reported a story under the headline: “Dr. Washington Dodge gives history of Titanic disaster at Commonwealth Club—breaks down in telling of the cries of the drowning in icy waters.”

“Any impression which I had that there were no survivors aboard was speedily removed from my mind by the faint, yet distinct cries which were wafted across the waters. Some there were in our boat who insisted that these cries came from occupants of the different lifeboats which were nearer the scene of the wreck than we were, as they called one to another. To my ear, however, they had but one meaning, and the awful fact was borne in upon me that many lives were perishing in those icy waters. With the disappearance of the steamer a great sense of loneliness and depression seemed to take possession of those in our boat.”

Dodge’s hometown newspaper, the San Francisco Bulletin, printed his account of the Titanic from the Hotel Wolcott on Friday, April 19, 1912: “Some of the passengers fought with such desperation to get into the lifeboats that the officers shot them, and their bodies fell into the ocean. . . . As the excitement began I saw an officer of the Titanic shoot down two steerage passengers who were endeavoring to rush the lifeboats. I have learned since that twelve of the steerage passengers were shot altogether, one officer shooting down six. . . . ” On April 19, 1912, the Baltimore Sun reported that Dodge said, “After we had gone over in the lifeboat, I heard as many as fifty shots fired, which was evidence to me that there had been scenes of dreadful fighting on board.” Dodge also said that he saw First Officer Willliam Murdoch shoot himself. “We could see from the distance that two boats were being made ready to be lowered. The panic was in the steerage, and it was that portion of the ship that the shooting was made necessary. Two men who attempted to rush beyond the restraint line were shot down by an officer who then turned the revolver on himself.

But Titanic steward Edenser Wheelton told a different story. While testifying during the U.S. Senate inquiry, Wheelton stood up for First Officer Murdoch: “I would like to say something about the bravery exhibited by the First Officer Mr. Murdoch. He was perfectly cool and very calm.”

After one of the crew lunches aboard the Titanic, probably on April 14, Wheelton tucked away a handwritten crew menu. Years later, back in England, Wheelton gave the menu to his niece, and it ended up in the hands of one of her husband’s employees. Main courses were Fried Sole, Grilled Cutlets, Grilled Chicken, Porterhouse Steak (a thick cut of beef from the back end of the cow), and Petite Maritime (lobster tail). French-Fried Potatoes were also on the menu. And there was stewed rhubarb and custard.

Culinary Spotlight

Rhubarb Custard Pie

1 stick of your favorite frozen pie crust dough 4 cups rhubarb, cut in ½-inch pieces 2 eggs 1 Tablespoon milk 1 cup all-purpose flour 1½ cups sugar, plus extra for lightly coating rhubarb and sprinkling on top of pie before baking 1 Tablespoon butter, plus enough to add pats to pie filling in pie plate

Using your fingers, lightly coat the bottom of the pie plate with a little bit of butter. Using a spoon, lightly coat the rhubarb pieces with a little sugar. Split pie crust in half; sprinkle flour on counter and roll out pie crusts into two circles (top crust and bottom crust). Place the bottom crust in the pie plate. Poke a few holes in the bottom crust with a fork for ventilation while baking. Put the rhubarb in the pie plate. Make the custard using a hand-held beater. Mix the eggs, milk, flour, and sugar together. Pour the egg mixture (the custard) over the rhubarb. Scatter six to eight tiny pats of butter around on the top of the rhubarb. Place the remaining pie crust on top. Using your fingers, scrunch together top and bottom pie crusts. Sprinkle pie with a light touch of sugar or a mix of cinnamon and sugar. Bake in 425 degree oven for forty-five minutes.

—Jeanne Kroeplin

About the Producers of the Series

Veronica Hinke is an expert in Food History & Culinary Narrative. She is the author of the acclaimed historical novel “The Last Night on the Titanic: Unsinkable Drinking, Dining & Style).” Veronica is passionate about sharing her love of history, culinary arts and most of all…. people. “Every food story I’ve ever written, always, at the core of each one, ended up being about the people, and that doesn’t seem to change. My book, “The Last Night on The Titanic,” is no different. Those stories of hope and resilience…I think that’s why the Titanic story is still alive today.”

Veronica’s mouthwatering books, short stories and magazine articles explore food history and the delicious culinary narratives that take you back in time. My heart calling is writing, teaching and speaking about the art of storytelling.

Scott Michael Rank, Ph.D., is the editor of History on the Net and host of the History Unplugged podcast. A historian of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, he is a publisher of popular history, a podcaster, and online course creator.

Cite This Article

"Last Night on the Titanic: Doctors and Con Artists" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/last-night-titanic-doctors-and-con-artists>

More Citation Information.